Classification view markdown

overview

- regressors don’t classify well

- e.g. outliers skew fit

- asymptotic classifier - assumes infinite data

- linear classifer $\implies$ boundaries are hyperplanes

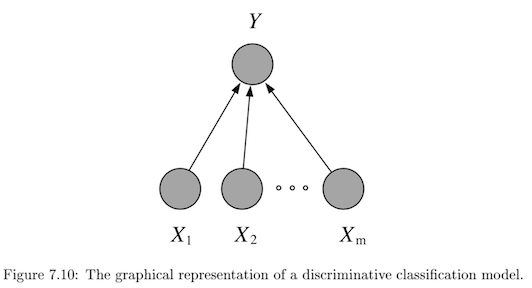

- discriminative - model $P(Y\vert X)$ directly

- usually lower bias $\implies$smaller asymptotic error

- slow convergence ~ $O(p)$

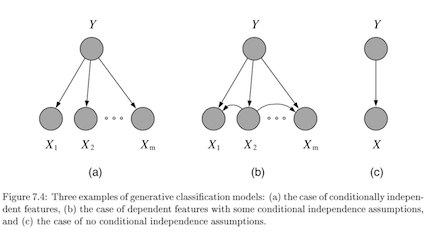

- generative - model $P(X, Y) = P(X\vert Y) P(Y)$

- usually higher bias $\implies$ can handle missing data

- this is because we assume some underlying X

- fast convergence ~ $O[\log(p)]$

- decision theory - models don’t require finding $p(y \vert x)$ at all

- usually higher bias $\implies$ can handle missing data

binary classification

- $\hat{y} = \text{sign}(\theta^T x)$

- usually $\theta^Tx$ includes bias term, but generally we don’t want to regularize bias

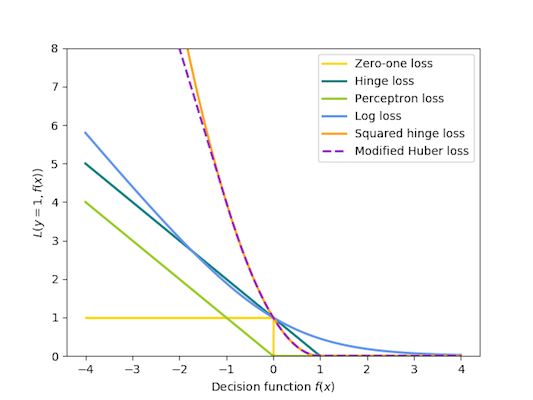

| Model | $\mathbf{\hat{\theta}}$ objective (minimize) |

|---|---|

| Perceptron | $\sum_i \max(0, -y_i \cdot \theta^T x_i)$ |

| Linear SVM | $\theta^T\theta + C \sum_i \max(0,1-y_i \cdot \theta^T x_i)$ |

| Logistic regression | $\theta^T\theta + C \sum_i \log[1+\exp(-y_i \cdot \theta^T x_i)]$ |

- svm, perceptron use +1/-1, logistic use 1/0

- perceptron - tries to find separating hyperplane

- whenever misclassified, update w

- can add in delta term to maximize margin

multiclass classification

- reducing multiclass (K categories) to binary

- one-against-all

- train K binary classifiers

- class i = positive otherwise negative

- take max of predictions

- one-vs-one = all-vs-all

- train $C(K, 2)$ binary classifiers

- labels are class i and class j

- inference - any class can get up to k-1 votes, must decide how to break ties

- flaws - learning only optimizes local correctness

- one-against-all

- single classifier - one hot vector encoding

- multiclass perceptron (Kesler)

- if label=i, want $\theta_i ^Tx > \theta_j^T x \quad \forall j$

- if not, update $\theta_i$ and $\theta_j$* accordingly

- kessler construction

- $\theta = [\theta_1 … \theta_k] $

- want $\theta_i^T x > \theta_j^T x \quad \forall j$

- rewrite $\theta^T \phi (x,i) > \theta^T \phi (x,j) \quad \forall j$

- here $\phi (x, i)$ puts x in the ith spot and zeros elsewhere

- $\phi$ is often used for feature representation

- define margin: $\Delta (y,y’) = \begin{cases} \delta& if : y \neq y’ \ 0& if : y=y’\end{cases}$

- check if $y=\text{argmax}_{y’} \theta^T \phi(x,y’) + \delta (y,y’)$

- multiclass SVMs (Crammer & Singer)

- minimize total norm of weights s.t. true label score is at least 1 more than second best label

- multinomial logistic regression = multi-class log-linear model (softmax on outputs)

- we control the peakedness of this by dividing by stddev

- multiclass perceptron (Kesler)

discriminative

logistic regression

-

$p(Y=1 x, \theta) = \text{logistic}(\theta^Tx)$ - assume Y ~ $\text{Bernoulli}(p)$ with $p=\text{logistic}(\theta^Tx$)

- can solve this online with GD of likelihood

- better to solve with iteratively reweighted least squares

- $Logit(p) = \log[p / (1-p)] = \theta^Tx$

- multiway logistic classification

-

assume $P(Y^k=1 x, \theta) = \frac{e^{\theta_k^Tx}}{\sum_i e^{\theta_i^Tx}}$, just as arises from class-conditional exponential family distributions

-

- logistic weight change represents change in odds

- fitting requires penalty on weights, otherwise they might not converge (i.e. go to infinity)

binary models

- probit (binary) regression

-

$p(Y=1 x, \theta) = \phi(\theta^Tx)$ where $\phi$ is the Gaussian CDF - pretty similar to logistic

-

- noise-OR (binary) model

- consider $Y = X_1 \lor X_2 \lor … X_m$ where each has a probability of failing

- define $\theta$ to be the failure probabilities

-

$p(Y=1 x, \theta) = 1-e^{-\theta^Tx}$

- other (binary) exponential models

-

$p(Y=1 x, \theta) = 1-e^{-\theta^Tx}$ but x doesn’t have to be binary -

complementary log-log model: $p(Y=1 x, \theta) = 1-\text{exp}[e^{-\theta^Tx}]$

-

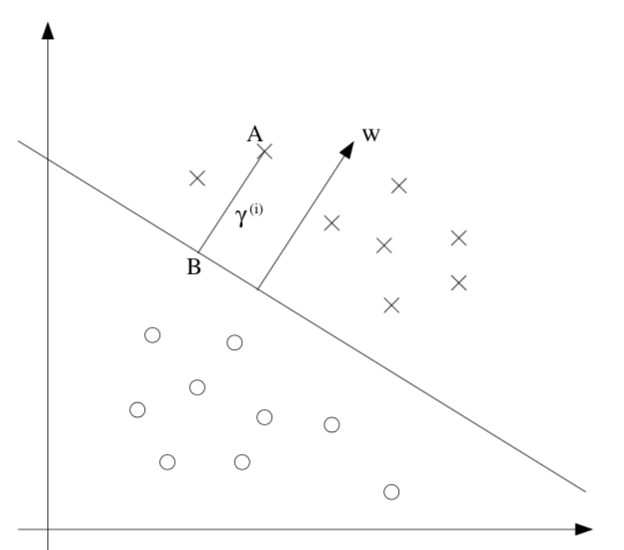

svms

- svm benefits

- maximum margin separator generalizes well

- kernel trick makes it very nonlinear

- nonparametric - retains training examples (although often get rid of many)

- at test time, can’t just store w - have to store support vectors

- $\hat{y} =\begin{cases} 1 &\text{if } w^Tx +b \geq 0 \ -1 &\text{otherwise}\end{cases}$

- $\hat{\theta} = \text{argmin} :\frac{1}{2} \vert \vert \theta\vert \vert ^2 \s.t. : y^{(i)}(\theta^Tx^{(i)}+b)\geq1, i = 1,…,m$

- functional margin $\gamma^{(i)} = y^{(i)} (\theta^T x +b)$

- limit the size of $(\theta, b)$ so we can’t arbitrarily increase functional margin

- function margin $\hat{\gamma}$ is smallest functional margin in a training set

- geometric margin = functional margin / $\vert \vert \theta \vert \vert $

- if $\vert \vert \theta \vert \vert =1$, then same as functional margin

- invariant to scaling of w

- derived from maximizing margin: \(\max \: \gamma \\\: s.t. \: y^{(i)} (\theta^T x^{(i)} + b) \geq \gamma, i=1,..,m\\ \vert \vert \theta\vert \vert =1\)

- difficult to solve, especially because of $\vert \vert w\vert \vert =1$ constraint

- assume $\hat{\gamma}=1$ ~ just a scaling factor

- now we are maximizing $1/\vert \vert w\vert \vert $

- functional margin $\gamma^{(i)} = y^{(i)} (\theta^T x +b)$

- soft margin classifier - allows misclassifications

- assigns them penalty proportional to distance required to move them back to correct side

-

min $\frac{1}{2} \theta ^2 \textcolor{blue}{ + C \sum_i^n \epsilon_i} \s.t. y^{(i)} (\theta^T x^{(i)} + b) \geq 1 \textcolor{blue}{- \epsilon_i}, i=1:m \ \textcolor{blue}{\epsilon_i \geq0, 1:m}$ - large C can lead to overfitting

- benefits

- number of parameters remains the same (and most are set to 0)

- we only care about support vectors

- maximizing margin is like regularization: reduces overfitting

- actually solve dual formulation (which only requires calculating dot product) - QP

- replace dot product $x_j \cdot x_k$ with kernel function $K(x_j, x_k)$, that computes dot product in expanded feature space

- linear $K(x,z) = x^Tz$

- polynomial $K (x, z) = (1+x^Tz)^d$

- radial basis kernel $K (x, z) = \exp(-r\vert \vert x-z\vert \vert ^2)$

- transforming then computing is O($m^2$), but this is just $O(m)$

- practical guide

- use m numbers to represent categorical features

- scale before applying

- fill in missing values

- start with RBF

- valid kernel: kernel matrix is Psd

decision trees / rfs - R&N 18.3; HTF 9.2.1-9.2.3

-

follow rules: predict based on prob distr. of points in same leaf you end up in

-

inductive bias

- prefer small trees

- prefer tres with high IG near root

-

good for certain types of problems

- instances are attribute-value pairs

- target function has discrete output values

- disjunctive descriptions may be required

- training data may have errors

- training data may have missing attributes

-

greedy - use statistical test to figure out which attribute is best

- split on this attribute then repeat

-

growing algorithm

- information gain - decrease in entropy

- weight resulting branches by their probs

- biased towards attributes with many values

- use GainRatio = Gain/SplitInformation

- can incorporate SplitInformation - discourages selection of attributes with many uniformly distributed values

- sometimes SplitInformation is very low (when almost all attributes are in one category)

- might want to filter using Gain then use GainRatio

- regression tree

- must decide when to stop splitting and start applying linear regression

- must minimize SSE

- information gain - decrease in entropy

-

can get stuck in local optima

-

avoid overfitting

-

empirically, early stopping is worse than overfitting then pruning (bc it doesn’t see combinations of useful attributes)

-

overfit then prune - proven more succesful

- reduced-error pruning - prune only if doesn’t decrease error on validation set

- $\chi^2$ pruning - test if each split is statistically significant with $\chi^2$ test

- rule post-pruning = cost-complexity pruning

- infer the decision tree from the training set, growing the tree until the training data is fit as well as possible and allowing overfitting to occur.

- convert the learned tree into an equivalent set of rules by creating one rule for each path from the root node to a leaf node.

- these rules are easier to work with, have no structure

- prune (generalize) each rule by removing any preconditions that result in improving its estimated accuracy.

- sort the pruned rules by their estimated accuracy, and consider them in this sequence when classifying subsequent instances.

-

-

incorporating continuous-valued attributes

- choose candidate thresholds which separate examples that differ in their target classification

- just evaluate them all

-

missing values

- could fill in most common value

- could assign values probabilistically

-

differing costs

- can bias the tree to favor low-cost attributes

- ex. divide gain by the cost of the attribute

- can bias the tree to favor low-cost attributes

-

high variance - instability - small changes in data yield changes to tree

-

many trees

- bagging = bootstrap aggregation - an ensemble method

- bootstrap - resampling with replacement

- train multiple models by randomly drawing new training data

- bootstrap with replacement can keep the sampling size the same as the original size

- random forest - for each split of each tree, choose from only m of the p possible features

- smaller m decorrelates trees, reduces variance

- RF with m=p $\implies$ bagging

- voting

- consensus: take the majority vote

- average: take average of distribution of votes

- reduces variance, better for improving more variable (unstable) models

- adaboost - weight models based on their performance

- bagging = bootstrap aggregation - an ensemble method

-

optimal classification trees - simultaneously optimize all splits, not one at a time

-

importance scores

- dataset-level

- for all splits where the feature was used, measure how much variance reduced (either summed or averaged over splits)

- the sum of importances is scaled to 1

- prediction-level: go through the splits and add up the changes (one change per each split) for each features

- note: this bakes in interactions of other variables

- ours: only apply rules based on this variable (all else constant)

- why not perturbation based?

- trees group things, which can be nice

- trees are unstable

- dataset-level

decision rules

- if-thens, rule can contain ands

- good rules have large support and high accuracy (they tradeoff)

- decision list is ordered, decision set is not (requires way to resolve rules)

- most common rules: Gini - classification, variance - regression

- ways to learn rules

- oneR - learn from a single feature

- sequential covering - iteratively learn rules and then remove data points which are covered

- ex rule could be learn decision tree and only take purest node

- bayesian rule lists - use pre-mined frequent patterns

- generally more interpretable than trees, but doesn’t work well for regression

- features often have to be categorical

- rulefit

- learns a sparse linear model with the original features and also a number of new features that are decision rules

- train trees and extract rules from them - these become features in a sparse linear model

- feature importance becomes a little stickier….

generative

gaussian class-conditioned classifiers

-

binary case: posterior probability $p(Y=1 x, \theta)$ is a sigmoid $\frac{1}{1+e^{-z}}$ where $z = \beta^Tx+\gamma$ - multiclass extends to softmax function: $\frac{e^{\beta_k^Tx}}{\sum_i e^{\beta_i^Tx}}$ - $\beta$s can be used for dim reduction

- probabilistic interpretation

- assumes classes are distributed as different Gaussians

- it turns out this yields posterior probability in the form of sigmoids / softmax

- only a linear classifier when covariance matrices are the same (LDA)

- otherwise a quadratic classifier (like QDA) - decision boundary is quadratic

- MLE for estimates are pretty intuitive

- decision boundary are points satisfying $P(C_i\vert X) = P(C_j\vert X)$

- regularized discriminant analysis - shrink the separate covariance matrices towards a common matrix

- $\Sigma_k = \alpha \Sigma_k + (1-\alpha) \Sigma$

- parameter estimation: treat each feature attribute and class label as random variables

- assume distributions for these

- for 1D Gaussian, just set mean and var to sample mean and sample var

- can use directions for dimensionality reduction (class-separation)

naive bayes classifier

- assume multinomial $Y$

-

with clever tricks, can produce $P(Y^i=1 x, \eta)$ again as a softmax - let $y_1,…y_l$ be the classes of Y

- want Posterior $P(Y\vert X) = \frac{P(X\vert Y)(P(Y)}{P(X)}$

- MAP rule - maximum a posterior rule

- use prior P(Y)

- given x, predict $\hat{y}=\text{argmax}_y P(y\vert X_1,…,X_p)=\text{argmax}_y P(X_1,…,X_p\vert y) P(y)$

- generally ignore constant denominator

- naive assumption - assume that all input attributes are conditionally independent given y

- $P(X_1,…,X_p\vert Y) = P(X_1\vert Y)\cdot…\cdot P(X_p\vert Y) = \prod_i P(X_i\vert Y)$

- learning

- learn $L$ priors $P(y_1),P(y_2),…,P(y_l)$

- for i in 1:$\vert Y \vert$

- learn $P(X \vert y_i)$

- for discrete case we store $P(X_j\vert y_i)$, otherwise we assume a prob. distr. form

- naive: $\vert Y\vert \cdot (\vert X_1\vert + \vert X_2\vert + … + \vert X_p\vert )$ distributions

- otherwise: $\vert Y\vert \cdot (\vert X_1\vert \cdot \vert X_2\vert \cdot … \cdot \vert X_p\vert )$

- smoothing - used to fill in $0$s

- $P(x_i\vert y_j) = \frac{N(x_i, y_j) +1}{N(y_j)+\vert X_i\vert }$

- then, $\sum_i P(x_i\vert y_j) = 1$

exponential family class-conditioned classifiers

- includes Gaussian, binomial, Poisson, gamma, Dirichlet

-

$p(x \eta) = \text{exp}[\eta^Tx - a(\eta)] h(x)$ - for classification, anything from exponential family will result in posterior probability that is logistic function of a linear function of x

text classification

- bag of words - represent text as a vector of word frequencies X

- remove stopwords, stemming, collapsing multiple - NLTK package in python

- assumes word order isn’t important

- can store n-grams

- multivariate Bernoulli: $P(X\vert Y)=P(w_1=true,w_2=false,…\vert Y)$

- multivariate Binomial: $P(X\vert Y)=P(w_1=n_1,w_2=n_2,…\vert Y)$

- this is inherently naive

- time complexity

- training O(n*average_doc_length_train+$\vert c\vert \vert dict\vert $)

- testing O($\vert Y\vert $ average_doc_length_test)

- implementation

- have symbol for unknown words

- underflow prevention - take logs of all probabilities so we don’t get 0

- $y = \text{argmax }\log :P(y) + \sum_i \log : P(X_i\vert y)$

instance-based (nearest neighbors)

- also called lazy learners = nonparametric models

- make Voronoi diagrams

- can take majority vote of neighbors or weight them by distance

- distance can be Euclidean, cosine, or other

- should scale attributes so large-valued features don’t dominate

- Mahalanobois distance metric accounts for covariance between neighbors

- in higher dimensions, distances tend to be much farther, worse extrapolation

- sometimes need to use invariant metrics

- ex. rotate digits to find the most similar angle before computing pixel difference

- could just augment data, but can be infeasible

- computationally costly so we can approximate the curve these rotations make in pixel space with the invariant tangent line

- stores this line for each point and then find distance as the distance between these lines

- ex. rotate digits to find the most similar angle before computing pixel difference

- finding NN with k-d (k-dimensional) tree

- balanced binary tree over data with arbitrary dimensions

- each level splits in one dimension

- might have to search both branches of tree if close to split

- finding NN with locality-sensitive hashing

- approximate

- make multiple hash tables

- each uses random subset of bit-string dimensions to project onto a line

- union candidate points from all hash tables and actually check their distances

- comparisons

- error rate of 1 NN is never more than twice that of Bayes error

likelihood calcs

single Bernoulli

-

$L(p) = P$[Train Bernoulli(p)]= $P(X_1,…,X_n\vert p)=\prod_i P(X_i\vert p)=\prod_i p^{X_i} (1-p)^{1-X_i}$ - $=p^x (1-p)^{n-x}$ where x = $\sum x_i$

- $\log[L(p)] = \log[p^x (1-p)^{n-x}]=x \log(p) + (n-x) \log(1-p)$

- $0=\frac{dL(p)}{dp} = \frac{x}{p} - \frac{n-x}{1-p} = \frac{x-xp - np+xp}{p(1-p)}=x-np$

- $\implies \hat{p} = \frac{x}{n}$

multinomial

- $L(\theta) = P(x_1,…,x_n\vert \theta_1,…,\theta_p) = \prod_i^n P(d_i\vert \theta_1,…\theta_p)=\prod_i^n factorials \cdot \theta_1^{x_1},…,\theta_p^{x_p}$- ignore factorials because they are always same

- require $\sum \theta_i = 1$

- $\implies \theta_i = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^n x_{ij}}{N}$ where N is total number of words in all docs

boosting

- adaboost

- freund & schapire

- reweight data points based on errs of previous weak learners, then train new classifiers

- classify as an ensemble

- gradient boosting

- leo breiman

- actually fits the residual errors made by the previous predictors

- newer algorithms for gradient boosting (speed / approximations)

- xgboost (2014 - popularized around 2016)

- implementation of gradient boosted decision trees designed for speed and performance

- things like caching, etc.

- light gbm (2017)

- can get gradient of each point wrt to loss - this is like importance for point (like weights in adaboost)

- when picking split, filter out unimportant points

- can get gradient of each point wrt to loss - this is like importance for point (like weights in adaboost)

- Catboost (2017)

- xgboost (2014 - popularized around 2016)

-

boosting with different cost function ($y \in {-1, 1}$, or for $L_2$Boost, also $y \in \mathbb R$)

Adaboost LogitBoost $L_2$Boost $\exp(y\hat{y})$ $\log_2 (1 + \exp(-2y \hat y ))$ $(y - \hat y)^2 / 2$