graphical models view markdown

Material from Russell and Norvig "Artifical Intelligence" 3rd Edition and Jordan "Graphical Models"

overview

- network types

- bayesian networks - directed

- undirected models

- latent variable types

- mixture models - discrete latent variable

- factor analysis models - continuous latent variable

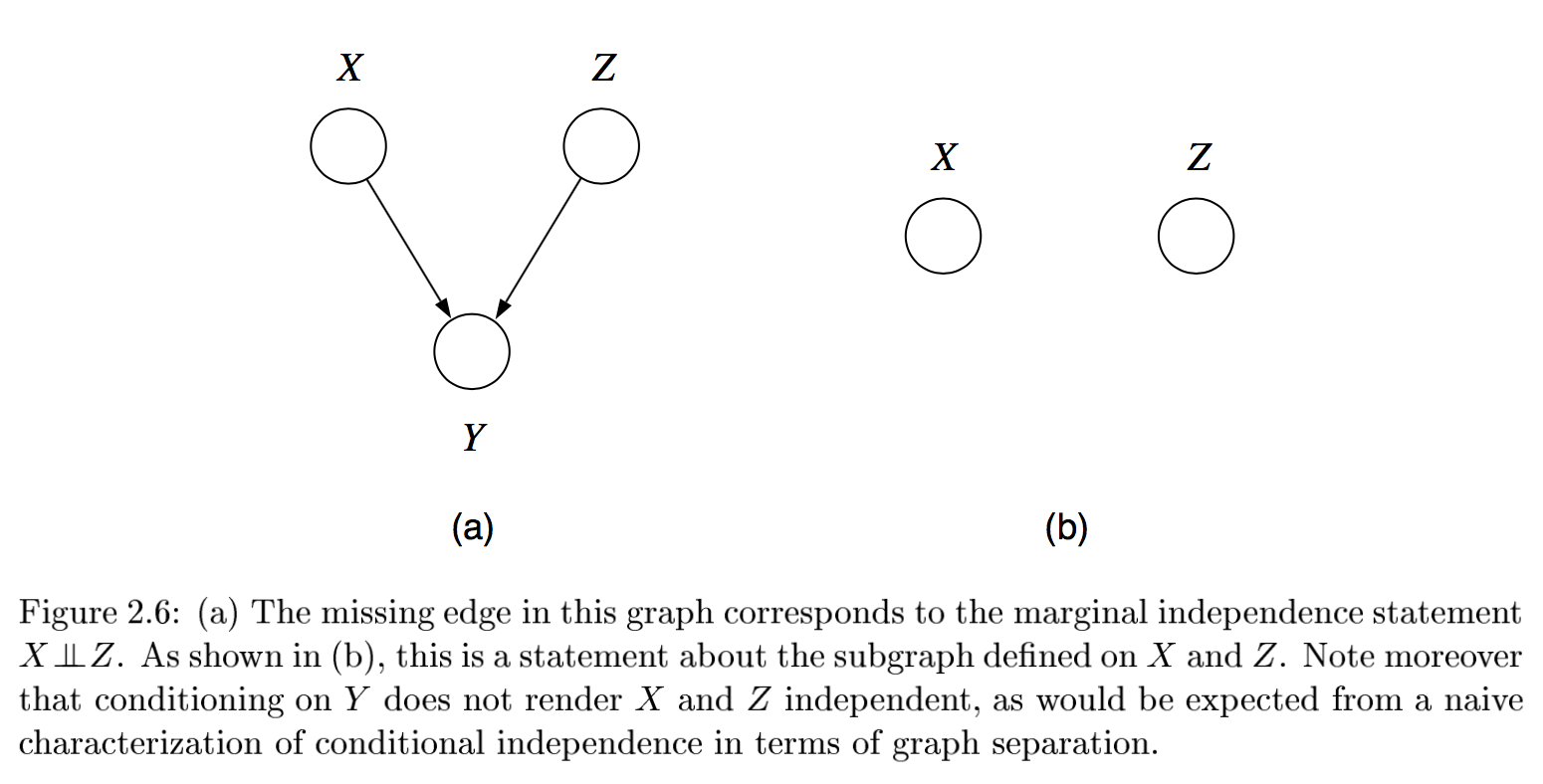

- graph representation: missing edges specify independence (converse is not true)

- encode conditional independence relationships

- helpful for inference

- compact representation of joint prob. distr. over the variables

- encode conditional independence relationships

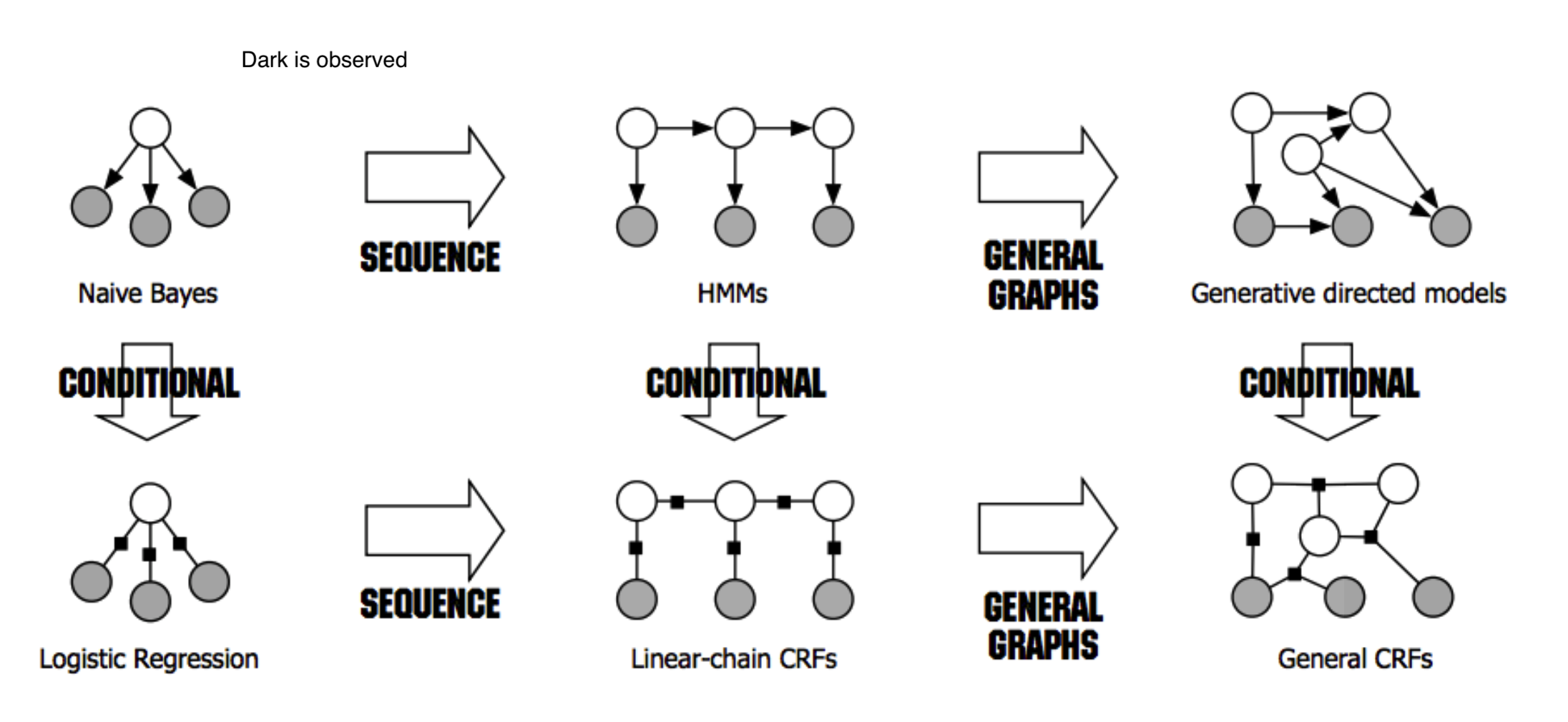

- dark is observed for HMMs, for other things unclear what it means

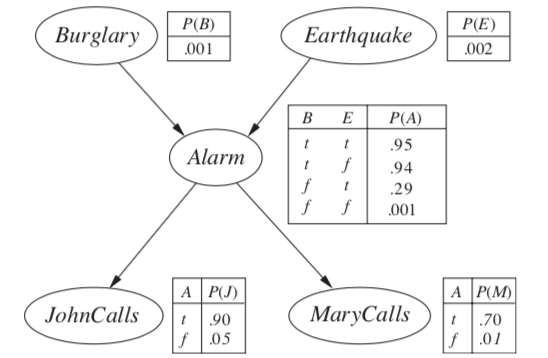

bayesian networks - R & N 14.1-5 + J 2

- examples

- causal model: causes $\to$ symptoms

- diagnostic model: symptoms $\to$ causes

- generally requires more dependencies

- learning

- expert-designed

- data-driven

- properties

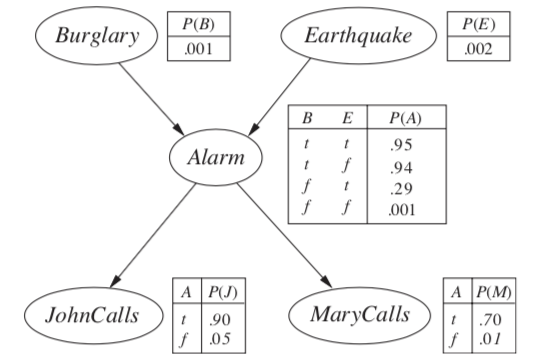

- each node is random variable

- weights as tables of conditional probabilities for all possibilities

- represented by directed acyclic graph

- joint distr: $P(X_1 = x_1,…X_n=x_n)=\prod_{i=1}^n P[X_i = x_i \vert Parents(X_i)]$

- markov condition: given parents, node is conditionally independent of its non-descendants

- marginally, they can still be dependent (e.g. explaining away)

- given its markov blanket (parents, children, and children’s parents), a node is independent of all other nodes

- markov condition: given parents, node is conditionally independent of its non-descendants

-

BN has no redundancy $\implies$ no chance for inconsistency

- forming a BN: keep adding nodes, and only previous nodes are allowed to be parents of new nodes

hybrid BN (both continuous & discrete vars)

- for continuous variables can sometimes discretize

- linear Gaussian - for continuous children

- parents all discrete $\implies$ conditional Gaussian - multivariate Gaussian given assignment to discrete variables

- parents all continuous $\implies$ multivariate Gaussian over all the variables, and a multivariate posterior distribution (given any evidence)

- parents some discrete, some continuous

- h is continuous, s is discrete; a, b, $\sigma$ all change when s changes

-

$P(c h,s) = N(a \cdot h + b, \sigma^2)$, so mean is linear function of h - discrete children (continuous parents) 1. probit distr - $P(buys|Cost=c) = \phi[(\mu - c)/\sigma]$ - integral of standard normal distr

- like a soft threshold 2. logit distr. - $P(buys|Cost=c) =s\left(\frac{-2 (\mu - c)}\sigma \right)$

- logistic function (sigmoid s) produces thresh

exact inference

- given assignment to evidence variables E, find probs of query variables X

- other variables are hidden variables H 1. enumeration - just try summing over all hidden variables

-

$P(X e) = \alpha P(X, e) = \alpha \sum_h P(X, e, h)$ - $\alpha$ can be calculated as $1 / \sum_x P(x, e)$

- $O(n \cdot 2^n)$

- one summation for each of n variables

- ENUMERATION-ASK evaluates in depth-first order: $O(2^n)$

- we removed the factor of n

- variable elimination - dynamic programming (see elimination)

- we removed the factor of n

-

$P(B j, m) = \alpha \underbrace{P(B)}{f_1(B)} \sum_e \underbrace{P(e)}{f_2(E)} \sum_a \underbrace{P(a B,e)}_{f_3(A, B, E)} \underbrace{P(j a)}_{f_4(A)} \underbrace{P(m a)}_{f_5(A)}$ - calculate factors in reverse order (bottom-up)

-

each factor is a vector with num entries = $\prod$ num_elements * num_values - when we multiply them, pointwise products

- ordering

- any ordering works, some are more efficient

- every variable that is not an ancestor of a query variable or evidence variable is irrelevant to the query

- complexity depends on largest factor formed

- clustering algorithms = join tree algorithms (see propagation factor graphs)

- join individual nodes in such a way that resulting network is a polytree

- polytree=singly-connected network - only 1 undirected paths between any 2 nodes

- time and space complexity of exact inference is linear in the size of the network

- holds even if the number of parents of each node is bounded by a constant

- can compute posterior probabilities in $O(n)$

- however, conditional probability tables may still be exponentially large

approximate inferences in BNs

- randomized sampling algorithms = monte carlo algorithms

- direct sampling methods:

- simplest - sample network in topological order

- rejection sampling - sample in order and stop once evidence is violated

-

want P(D A) - sample N times, throw out samples where A is false

- return probability of D being true

- this is slow

-

- likelihood weighting - fix evidence to be more efficient

- generating a sample

- fix our evidence variables to their observed values, then simulate the network

- can’t just fix variables - distr. might be inconsistent

- calculate W = prob of sample being generated

- when we get to an evidence variable, multiply by prob it appears given its parents

- for each observation

- if positive, Count = Count + W

- Total = Total + W

- return Count/Total

- this way we don’t have to throw out wrong samples

- doesn’t solve all problems - evidence only influences the choice of downstream variables

- generating a sample

- Markov chain monte carlo - ex. Gibbs sampling, Metropolis-Hastings

- fix evidence variables

- sample a nonevidence variable $X_i$ conditioned on the current values of its Markov blanket

- repeatedly resample one-at-a-time in arbitrary order

- why it works

- the sampling process settles into a dynamic equilibrium where time spent in each state is proportional to its posterior probability

- provided transition matrix q is ergodic - every state is reachable and there are no periodic cycles - only 1 steady-state soln

- 2 steps

- create markov chain with write stationary distr.

- draw samples by simulating the chain

- methods

- 0th order methods - query density

- metropolized random walk

- ball walk

- hit-and-run algorithm

- 1st order methods - uses gradient of the density

- Gibbs: we have conditionals

- metropolis adjusted langevin algorithm (MALA) = langevin monte carlo

- use gradient to propose new states

- accept / reject using metropolis-hastings algorithm

- unadjusted langevin algorithm (ULA)

- hamiltonian monte carlo (neal, 2011) - log-concave distr. density (analog of convexity)

- $\pi(x) = \frac{e^{-f(x)}}{\int e^{-f(y)}dy}$

- examples: normal distr., exponential distr., Laplace distr.

- variational inference - formulate inference as optimization

- good intro paper

- minimize KL-divergence between observed samples and assumed distribution

- the actual KL is hard to minimize so instead we maximize the ELBO, which is equivalent

- do this over a class of possible distrs.

- variational inference tends to be faster, but may not be as good as MCMC

conditional independence properties

-

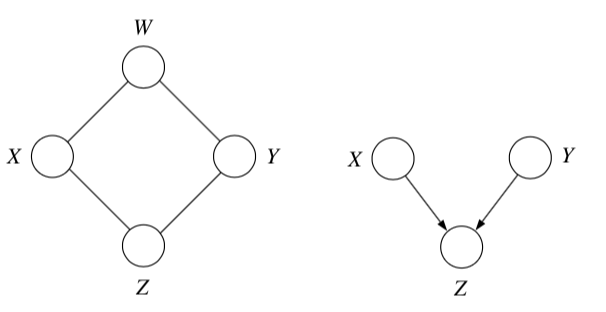

multiple, competing explanations (“explaining-away”)

- in fact any descendant of the base of the v suffices for explaining away

-

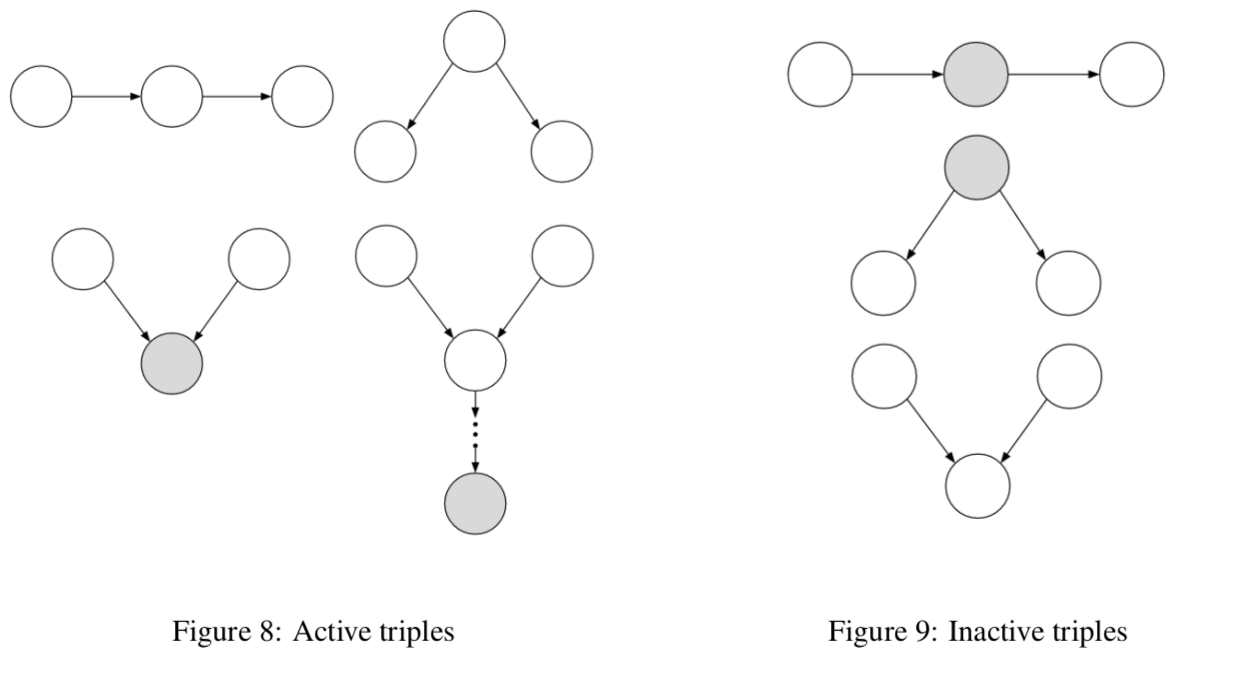

d-separation = directed separation

-

Bayes ball algorithm - is $( X_A \perp X_B ) X_C$? - initialize

- shade $X_C$

- place ball at each of $X_A$

- if any ball reaches $X_B$, then not conditionally independent

- rules

- balls can’t pass through shaded unless shaded is at base of v

- balls pass through unshaded unless unshaded is at base of v

- initialize

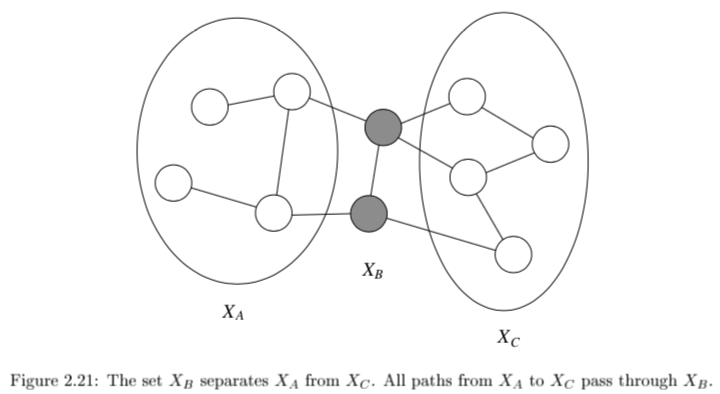

undirected

-

$X_A \perp X_C X_B$ if the set of nodes $X_B$ separates the nodes $X_A$ from $X_C$

- can’t convert directed / undirected

- factor over maximal cliques (largest sets of fully connected nodes)

- potential function $\psi_{X_C} (x_C)$ function on possible realizations $x_C$ of the maximal clique $X_C$

- non-negative, but not a probability (specifying conditional probs. doesn’t work)

- commonly let these be exponential: $\psi_{X_C} (x_C) = \exp(-f_C(x_C))$

- yields energy $f(x) = \sum_C f_C(x_C)$

- yields Boltzmann distribution: $p(x) = \frac{1}{Z} \exp (-f(x))$

- $p(x) = \frac{1}{Z} \prod_{C \in Cliques} \psi_{X_C}(x_c)$

- $Z = \sum_x \prod_{C \in Cliques} \psi_{X_C} (x_C)$

- reduced parameterizations - impose constraints on probability distributions (e.g. Gaussian)

- if x is dependent on all its neighbors

- Ising model - if x is binary

- Potts model - x is multiclass

elimination - J 3

- the elimination algorithm is for probabilistic inference

-

want $p(x_F x_E)$ where E and F are disjoint - any var that is not ancestor of evidence or ancestor of query is irrelevant

-

- here, let $X_F$ be a single node

- notation

- define $m_i (x_{S_i})$ = $\sum_{x_i}$ where $x_{S_i}$ are the variables, other than $x_i$, that appear in the summand

- define evidence potential $\delta(x_i, \bar{x_i})$ is defined as $x_i == \bar{x_i}$

- then \(g(\bar{x_i}) = \sum_{x_i} \delta (x_i, \bar{x_i})\)

- for a set $\delta (x_E, \bar{x_E}) = \prod_{i \in E} \delta (x_i, \bar{x_i})$

- lets us define $p(x, \bar{x}_E) = p^E(x) = p(x) \delta (x_E, \bar{x_E})$

- undirected graphs

- $\psi_i^E(x_i) \triangleq \psi_i(x_i) \delta(x_i, \bar{x}_i)$

- this lets us write $p^E (x) = \frac{1}{Z} \prod_{c\in C} \psi^E_{X_c} (x_c)$

- can ignore z since this is unnormalized anyway

- to find conditional probability, divide by all sum of $p^E(x)$ for all values of E

- in actuality don’t compute the product, just take the correct slice

- eliminate algorithm

- initialize: choose an ordering with query last

- evidence: set evidence vars to their values

- update: loop over element $x_i$ in ordering

- let $\phi_i(x_{T_i})$ be product of all potentials involving $x_i$

- sum over the product of these potentials $m_i(x_{S_i}) = \sum_x \phi_i(x_{T_i})$

-

normalize: $p(x_F \bar{x}E) = \phi_F(x_F) / \sum{x_F} \phi_F (x_F)$

- undirected graph elimination algorithm

- for directed graph, first moralize

- for each node connect its parents

- drop edges orientation

- for each node X

- connect all remaining neighbors of X

- remove X from graph

- for directed graph, first moralize

- reconstituted graph - same nodes, includes all edges that were added

- elimination cliques - includes X and its neighbors when X is removed

- computational complexity is the exponential in the number of variables in the elimination clique

- involves treewidth - one less than smallest achievable value of cardinality of largest elimination clique

- range over all possible elimination orderings

- NP-hard to find elimination ordering that achieves the treewidth

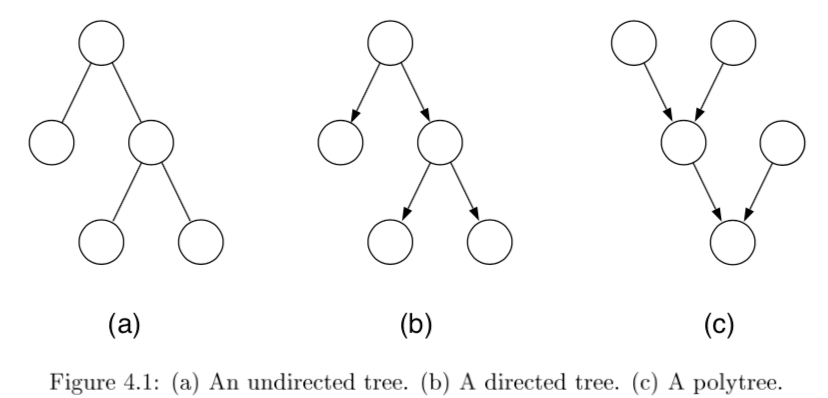

propagation factor graphs - J 4

- tree - undirected graph in which there is exactly one path between any pair of nodes

- if directed, then moralized graph should be a tree

- polytree - directed graph that reduces to an undirected tree if we convert each directed edge to an undirected edge

-

\[p(x) = \frac{1}{Z} \left[ \prod_{i \in V} \psi (x_i) \prod_{(i,j)\in E} \psi (x_i,x_j) \right]\]

- for directed, root has individual prob and others are conditionals

- can once again use evidence potentials for conditioning

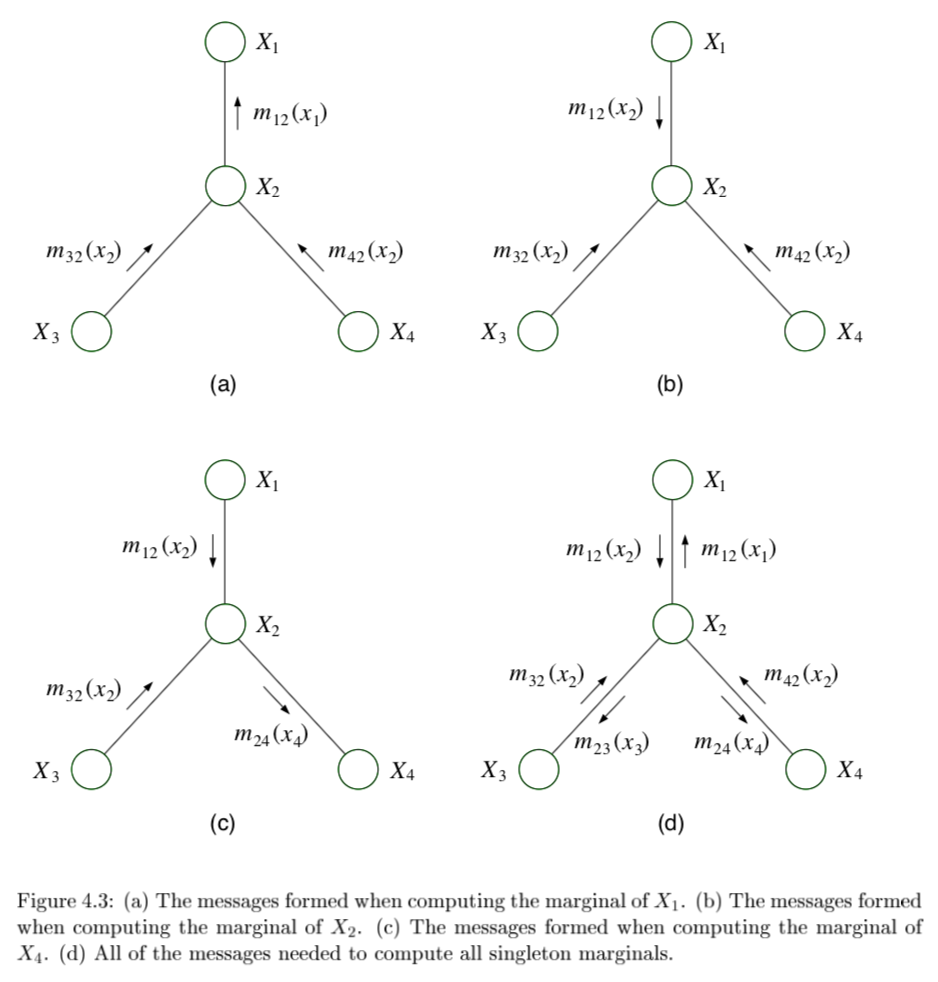

probabilistic inference on trees

- eliminate algorithm through message-passing

- ordering I should be depth-first traversal of tree with f as root and all edges pointing away

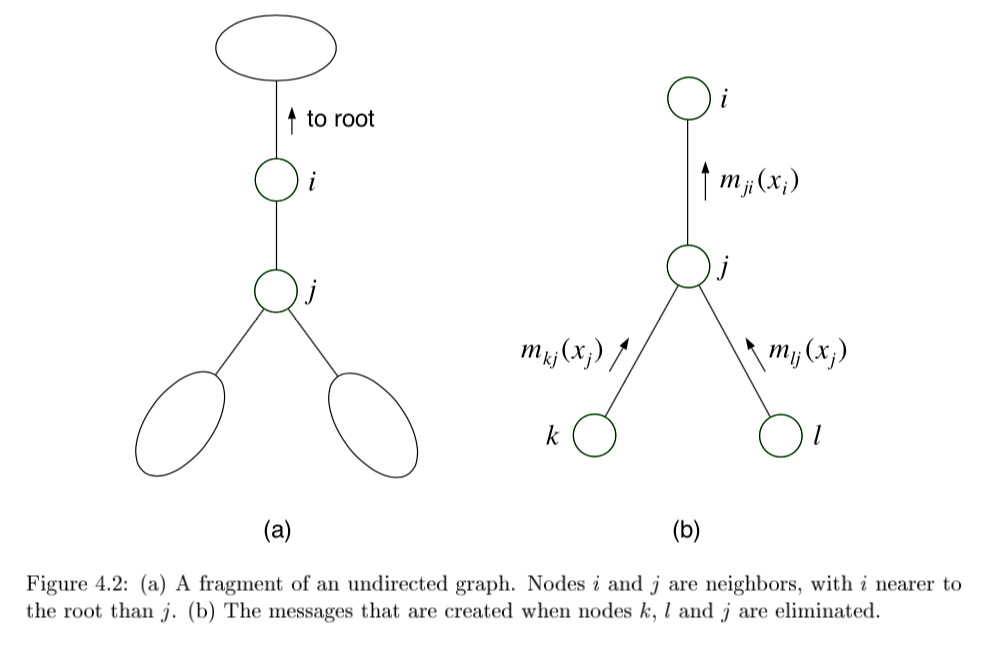

- message $m_{ji}(x_i)$ from $j$ to $i$ =intermediate factor

- ordering I should be depth-first traversal of tree with f as root and all edges pointing away

-

2 key equations

- $m_{ji}(x_i) = \sum_{x_j} \left( \psi^E (x_j) \psi (x_i, x_j) \prod_{k \in N(j) \backslash i} m_{kj} (x_j) \right)$

-

$p(x_f \bar{x}E) \propto \psi^E (x_f) \prod{e \in N(f)} m_{ef} (x_f) $

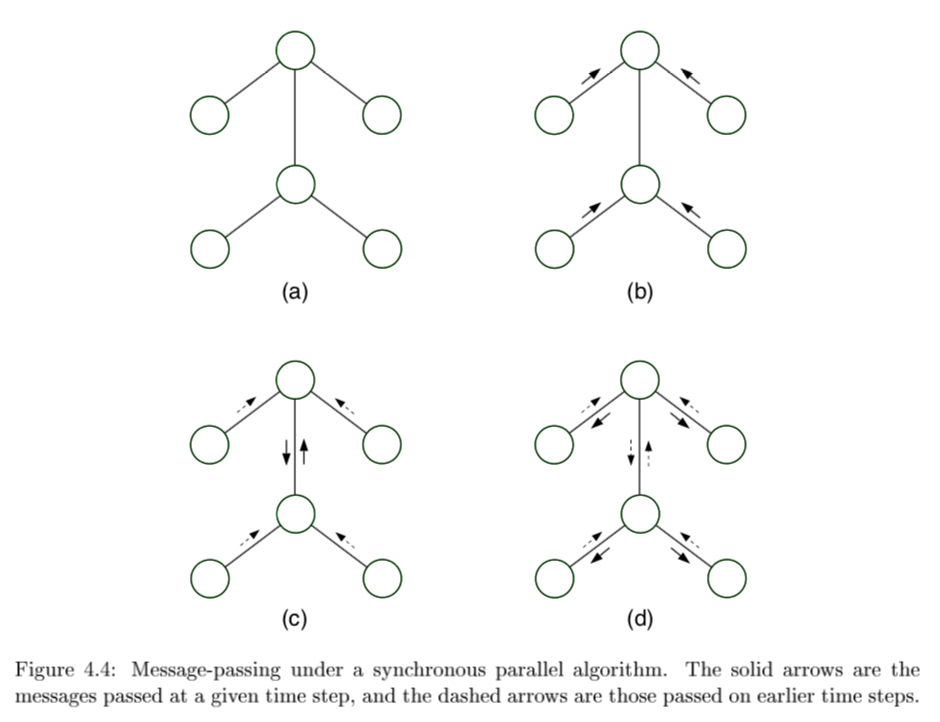

- sum-product = belief propagation - inference algorithm

-

computes all single-node marginals (for certain classes of graphs) rather than only a single marginal

-

only works in trees or tree-like graphs

-

-

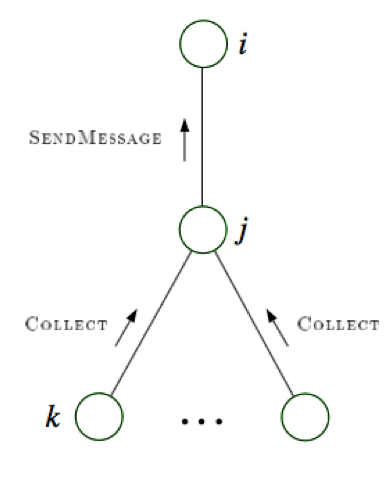

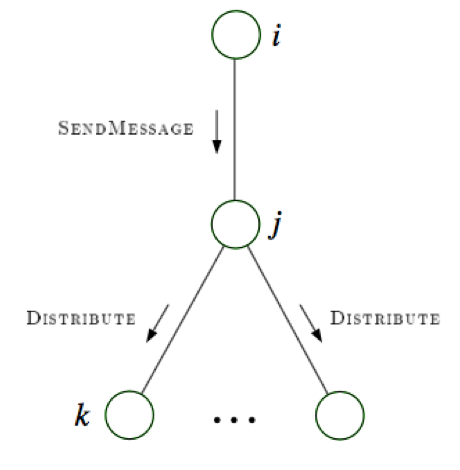

message-passing protocol - a node can send a message to a neighboring node when, and only when, it has received messages from all of its other neighbors (parallel algorithm)

- evidence(E)

- choose root

- collect: send messages evidence to root

- distribute: send messages root back out

-

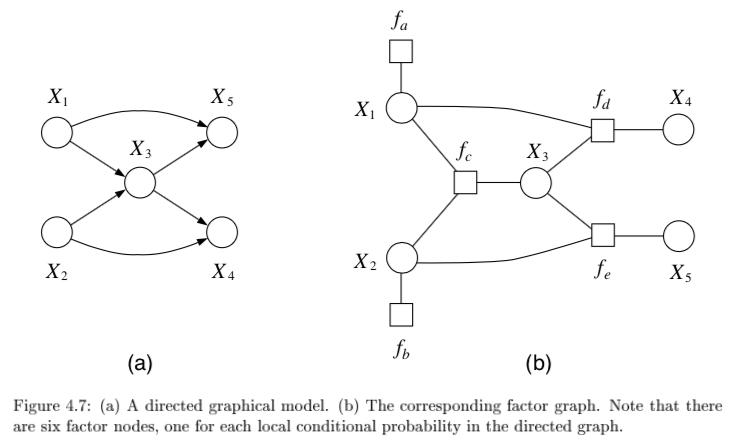

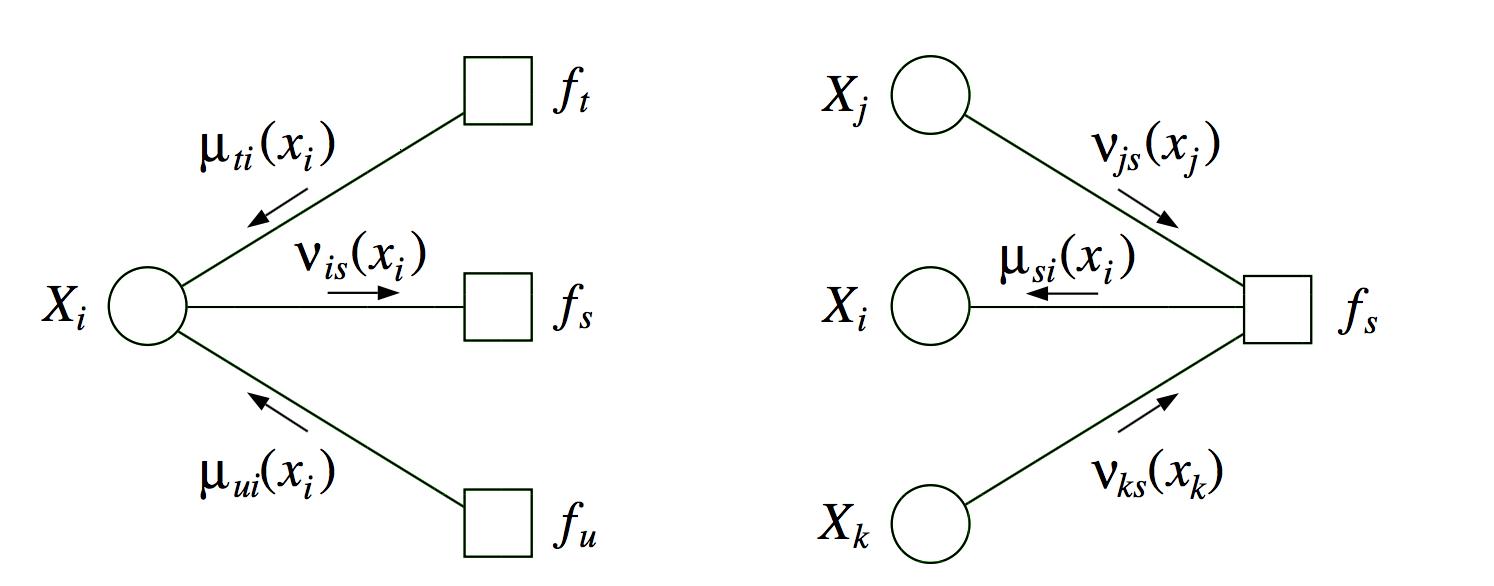

factor graphs

- factor graphs capture factorizations, not conditional independence statements

- ex $\psi (x_1, x_2, x_3) = f_a(x_1,x_2) f_b(x_2,x_3) f_c (x_1,x_3)$ factors but has no conditional independence

- \[f(x_1,...,x_n) = \prod_s f_s (x_{C_s})\]

- neighborhood N(s) for a factor index s is all the variables the factor references

- neighborhood N(i) for a node i is set of factors that reference $x_i$

- provide more fine-grained representation of prob. distr.

- could add more nodes to normal graphical model to do this

- ex $\psi (x_1, x_2, x_3) = f_a(x_1,x_2) f_b(x_2,x_3) f_c (x_1,x_3)$ factors but has no conditional independence

- factor tree - if factors are made nodes, resulting undirected graph is tree

- two kinds of messages (variable-> factor & factor-> variable)

- run all the factor $\to$ variables first

- \[p(x_i) \propto \prod_{s \in N(i)} \mu_{si} (x_i)\]

- if a graph is originally a tree, there is little to be gained from factor graph framework

- sometimes factor graph is factor tree, but original graph is not

maximum a posteriori (MAP)

-

want $\max_{x_F} p(x_F \bar{x}_E)$ - MAP-eliminate algorithm is very similar to before

- initialize - choose ordering

- evidence - set evidence

- update - for each take max over variable and make new factor

- maximum - marginalize

- products of probs tend to underflow, so take $\max_x \log p^E (x)$

- can also derive a max-product algorithm for trees

- find $\text{argmax}_x p^E (x)$

- can solve by keeping track of maximizing values of variables in max-product algorithm

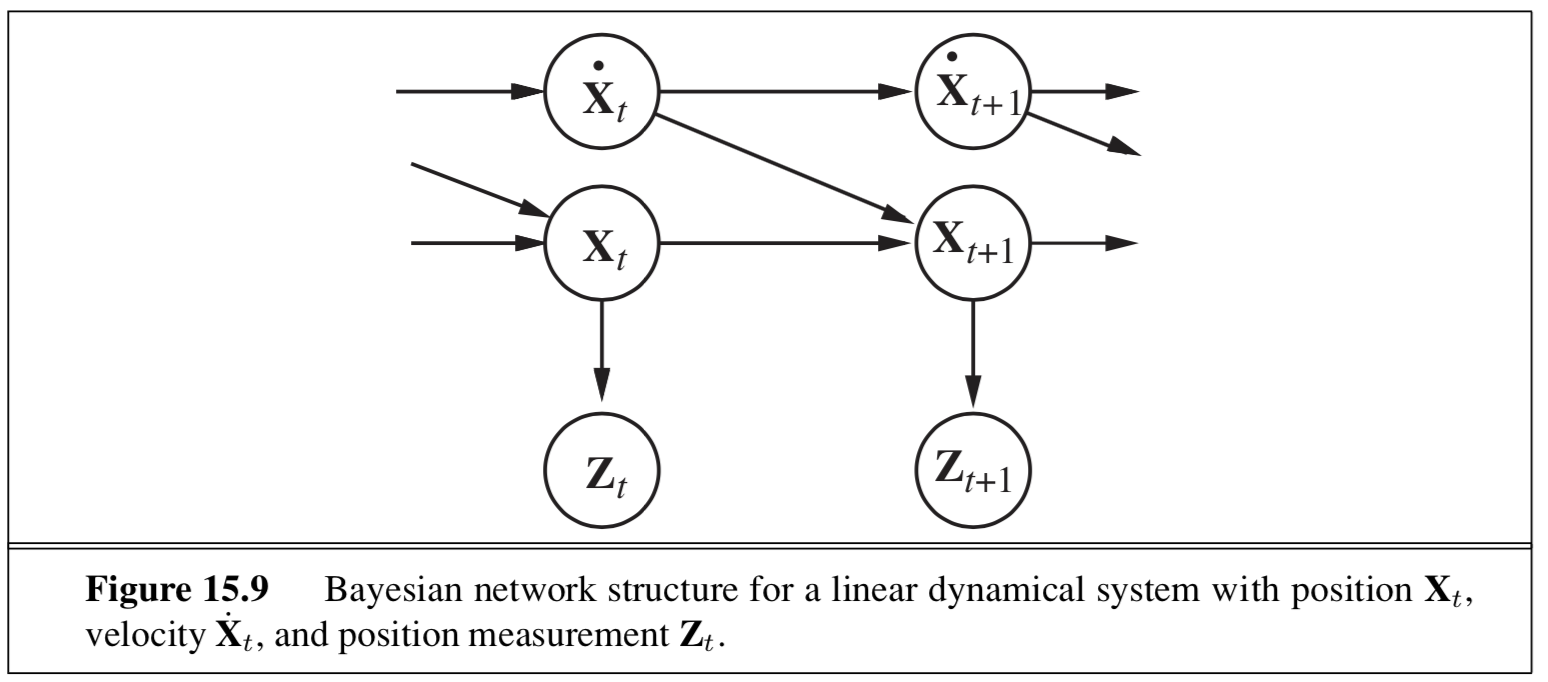

dynamic bayesian nets

- dynamic bayesian nets - represents a temporal prob. model

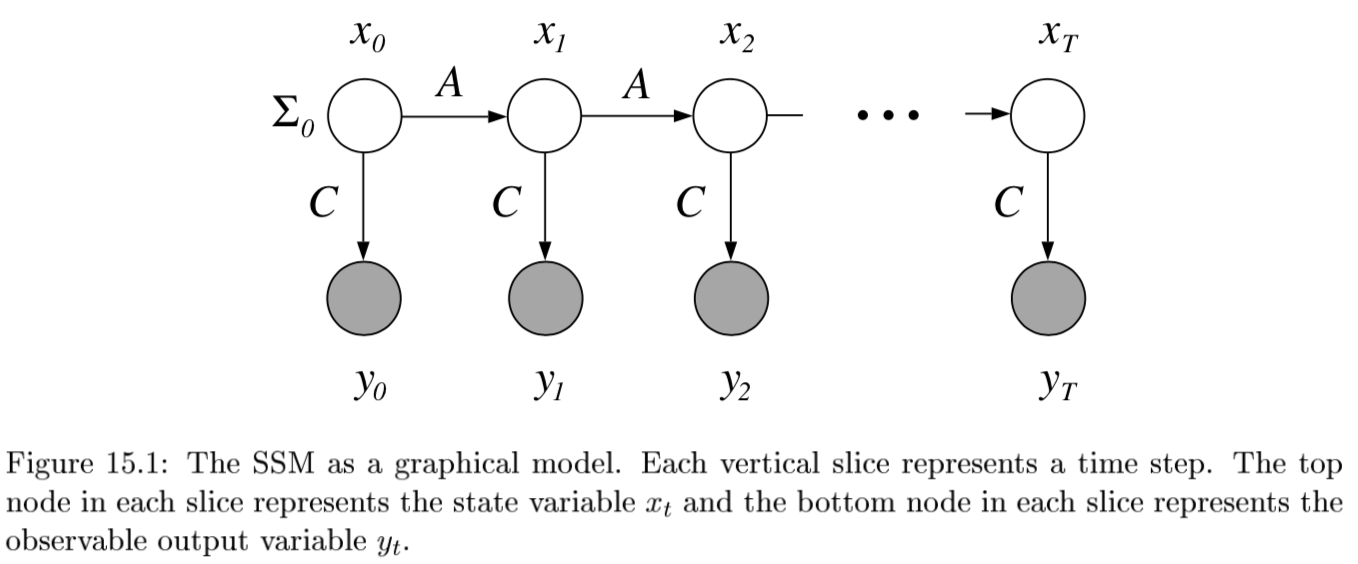

state space model

-

state space model

-

$P(X_{0:t}, E_{1:t}) = P(X_0) \prod_{i} \underbrace{P(X_i X_{i-1}) }_{\text{transition model}} : \underbrace{P(E_i X_i)}_{\text{sensor model}}$ -

agent maintains belief state of state variables $X_t$ given evidence variables $E_t$

-

improve accuracy

- increase order of Markov transition model

- increase set of state variables (can be equivalent to 1)

- hard to maintain state variables over time, want more sensors

-

-

4 inference problems (here $\cdot$ is elementwise multiplication)

-

filtering = state estimation - compute $P(X_t e_{1:t})$ - recursive estimation: $$\underbrace{P(X_{t+1} e_{1:t+1})}{\text{new state}} = \alpha : \underbrace{P(e{t+1} X_{t+1})}{\text{sensor}} \cdot \underset{x_t}{\sum} : \underbrace{P(X{t+1} x_t)}_{\text{transition}} \cdot \underbrace{P(x_t e_{1:t})}_{\text{old state}}$$ where $\alpha$ normalizes probs -

prediction - compute $P(X_{t+k} e_{1:t})$ for $k>0$

-

-

$\underbrace{P(X_{t+k+1} e_{1:t})}{\text{new state}} = \sum{x_{t+k}} \underbrace{P(X_{t+k+1} x_{t+k})}{\text{transition}} \cdot \underbrace{P(x{t+k} e_{1:t})}_{\text{old state}}$

-

smoothing - compute $P(X_{k} e_{1:t})$ for $0 < k < t$ -

2 components $P(X_k e_{1:t}) = \alpha \underbrace{P(X_k e_{1:k})}{\text{forward}} \cdot \underbrace{P(e{k+1:t} X_k)}_{\text{backward}}$ - forward pass: filtering from $1:t$ 2. backward pass from $t:1$ $\underbrace{P(e_{k+1:t}|X_k)}{\text{sensor past k}} = \sum{x_{k+1}} \underbrace{P(e_{k+1}|x_{k+1})}{\text{sensor}} \cdot \underbrace{P(e{k+2:t}|x_{k+1})}{\text{recursive call}} \cdot \underbrace{P(x{k+1}|X_k)}_{\text{transition}}$ 3. this is called the forward-backward algo(also there is a separate algorithm that doesn’t use the observations on the backward pass)

-

-

most likely explanation - $\underset{x_{1:t}}{\text{argmax}}:P(x_{1:t} e_{1:t})$ -

Viterbi algorithm: $\underbrace{\underset{x_{1:t}}{\text{max}} : P(x_{1:t}, X_{t+1} e_{1:t+1})}{\text{mle x}} = \alpha : \underbrace{P(e{t+1} X_{t+1})}{\text{sensor}} \cdot \underset{x_t}{\text{max}} \left[ : \underbrace{P(X{t+1} x_t)}{\text{transition}} \cdot \underbrace{\underset{x{1:t-1}}{\text{max}} :P(x_{1:t-1}, x_{t+1} e_{1:t})}_{\text{max prev state}} \right]$ - complexity

- K = number of states

- M = number of observations

- n = length of sequence

- memory - $nK$

- runtime - $O(nK^2)$

-

-

learning - form of EM

- basically just count (maximizing joint likelihood of input and output)

- initial state probs $\frac{count(start \to s)}{n}$

-

$P(x’ x) = \frac{count(s \to s’)}{count(s)}$ -

$P(y x) = \frac{count (x \to y)}{count(x)}$

hmm

- state is a single discrete process

- transitions are all matrices (and no zeros in sensor model)$\implies$ forward pass is invertible so can use constant space

- online smoothing (with lag)

- ex. robot localization

kalman filtering

- state is continuous

- ex.

- type of nodes (real-valued vectors) and prob model (linear-Gaussian) changes from HMM

- 1d example: random walk

- state nodes: $x_{t+1} = Ax_t + Gw_t$

- output nodes: $y_t = Cx_t+v_t$

- x is linear Gaussian

- w is noise Gaussian

- y is linear Gaussian

- doing the integral for prediction involves completing the square

- properties

- new mean is weighted mean of new observation and old mean

- update rule for variance is independent of the observation

- variance converges quickly to fixed value that depends only on $\sigma^2_x, \sigma^2_z$

- Lyapunov eqn: evolution of variance of states

- information filter - mathematically the same but different parameterization

- extended Kalman filter

- works on nonlinear systems

- locally linear

- switching Kalman filter - multiple Kalman filters run in parallel and weighted sum of predictions is used

- ex. one for straight flight, one for sharp left turns, one for sharp right turns

- equivalent to adding discrete “maneuver” state variable

general dbns

- can be better to decompose state variable into multiple vars

- reduces size of transition matrix

- transient failure model - allows probability of sensor giving wrong value

- persistent failure model - additional variable describing status of battery meter

- exact inference - våariable elimination mimics recursive filtering

- still difficult

- approximate inference - modification of likelihood weighting

- use samples as approximate representation of current state distr.

- particle filtering - focus set of samples on high-prob regions of the state space

- consistent

- sample a state

- sample the next state given the previous state

-

weight each sample by $P(e_t x_t)$ - resample based on weight

structure learning

- conditional correlation - inverse covariance matrix = precision matrix

- estimates only good when $n » p$

- eigenvalues are not well-approximated

- often enforce sparsity

- ex. threshold each value in the cov matrix (set to 0 unless greater than thresh) - this threshold can depend on different things

- can also use regularization to enforce sparsity

- POET doesn’t assume sparsity